By Brandon James Anderson, Shawn Mangerino, and Michael C. Brickey

All rights reserved.

“The present period of history is one of the Wall. Concrete, bureaucratic, surveillance, security, racist walls. Everywhere the walls separate the desperate poor from those who hope against hope to stay relatively rich. The walls cross every sphere, from crop cultivation to health care. They exist too in the richest metropolises of the world. The Wall is the front line of what, long ago, was called the Class War.”

John Berger, Hold Everything Dear (2007)

“The mundane elements of planning and architecture

have become tactical tools and means of dispossession.”

Eyal Weizman, Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation (2007)

Walls have grown familiar to the present human condition. Perhaps the most memorable metaphorical wall was the Iron Curtain. Then there are those lines on our mental town maps-streets that divide one part of town from another. And there are the walls that occupy our social terrain such as the barriers to racial equality and the limits to economic opportunity.

Author John Berger and architectural critic Eyal Weizmann use the Wall in Israel as both a real marker of separation and symbolic metaphor for oppression. Through Berger’s “dispatches on reality” and Weizmann’s consideration of the “architecture of occupation,” both authors describe Palestine as a place where the Muslims are not only a people without a nation, but live a life marked by the Wall and various other blockades, checkpoints, restricted roads, and inaccessible highways. Berger and Weizmann note how these various walls have continuously divided Palestinian territory into smaller, more isolated parcels. The Israeli forces have given the world the false impression that their occupation is a necessary defensive measure. Through Berger’s “dispatches,” those disconnected from the situation get a vivid sense of the oppression at work in this modern version of a “separate but equal” policy. Weizmann refers to the territorial and social separation as an “elastic geography,” whereby the expansion of Israeli settlements and the construction of its divisive infrastructure have created a non-fixed border between the two states. As Weizmann puts it, “War was only over because it was now everywhere.”

What follows serves as a partial overview, with examples, of the ways governments, societies, and corporations erect and manage walls, structures, and policies as means of oppression. Through these critical discourses and dispatches we hope to show how individuals in these wall-building societies, have grown complicit in the walls’ construction, thus, contributing to their reinforcement.

*

Concrete, bureaucratic, surveillance, security, racist walls. (Berger)

I mentioned to the man I was from St. Louis. With the Budweiser and Guinness neon signs reflecting in his teary beer eyes, he leaned back in his chair and looked out the window. Moving his hands in an arc pattern, he said, “Ah, yes. St. Louie. I know the Arch.” Looking at me now he smiled and gestured as if I had something to do with what he was about to say: “Very famous.” This man from Ireland, and for that matter people throughout the world, know St. Louis by its most recognizable structure, and understandably.

The “Gateway to the West” adorns nearly every postcard and published photo of the city. With few exceptions, people take these skyline photographs from across the Mississippi River in East St. Louis, Illinois. Unfortunately, the residents of East St. Louis do not share this postcard panorama. For the last fifty years, residents of the “East Side” have lived with the looming infrastructure of the interstate. From their point of view, the Gateway to the West is sealed shut with concrete and steel. They are walled in.

Gray is the dominant color of the interstate underbelly, and even on the sunniest days grayness occupies the residents’ westward and skyward vision. The citizens of the floodplain live in forced intimacy with the freeway’s concrete pylons.

The interstate is as dominant a feature as it is a common characteristic of the American landscape. Eyal Weizmann suggests that we take a critical look at even the most common characteristics of the built environment in order to assess how principles of design correspond to policies of oppression. The interstate is a highly visible wall; it is the most visible example of the architecture of oppression. It occludes, pervades, and prevents. Commuters along the East St. Louis Expressway are not inclined to look down, to see the racialized poverty directly beneath them. Beneath the strategically designed mass of interstate exchanges, overpasses, underpasses, onramps, and off-ramps, is a living example of the local underclass ignored in every neoliberal economics class. As suburbanites commute from their fenced and gated communities to the secured and monitored corporate offices of St. Louis, they whisk by and over an impoverished population with their eyes fixed on the Arch.

Doubtless, drivers see Eero Saarinen’s beacon of modernism as a symbol of progress, a representation of technological growth, and testament to human potential. The structure itself speaks loudly of the future and the belief that humans and their modern civilization have the wherewithal to progress, move forward. Built during the Cold War, the Arch subscribed to the myth that capitalist growth defeats communist stagnation.

*

The walls cross every sphere, from crop cultivation to health care. (Berger)

Reporting from Washington:

Genetically modified foods are not new. Monsanto, a chemical-cum-biotechnology company, entered the agricultural industry in the 1990s and since then farmers’ traditions and practices with seed and soil are nearing obliteration. Genetically modified (GM) foods have been sold commercially since 1994. And opponents of GM agriculture have been crying foul.

“The sole purpose of genetically engineered seeds is to increase profits for these corporations,” says one researcher. “Whether that’s through taking advantage of US patent laws or through the ravaging of the farmers that are their customers, it makes no difference to these companies.”

Ravaged is the way some farmers feel. “It’s to the point where us farmers are becoming enslaved to companies like Monsanto,” says an Iowa farmer. “I mean, where else are we going to get the seed? It’s all the same companies.”

Biotech companies contend that the genetically modified seeds are a scientific advancement meant to accelerate agricultural and, thus, societal progress. “For as long as farming has occurred, there have been ideas and processes used to promote growth,” says a biotech spokesman. “For centuries farmers used yeast to help the rate of plantation of crops. What we’re seeing now is essentially the same thing.”

Traders and farmers point out that GM seeds are in no way related to the practices farmers have employed for centuries. Mexico, in fact, has banned GM seeds in an effort to maintain the traditions of Mexican farming. According to an analyst, “This is the problem. If laws push back against these companies, they will go to other countries where they can file patents and take advantage of weak legislation. And they’ll take their suicide seeds with them.”

It’s that last phrase that is starting to become an issue of contention in the field — suicide seeds. “It’s a false term that’s been used ignorantly,” says a Monsanto spokesman. These seeds are designed to be used in conjunction with our other products, such as RoundUp.”

RoundUp is a moneymaker pesticide for the company. It has been sold in large quantities to individual and commercial farms all over America and across the globe. RoundUp Ready seeds require RoundUp in order to germinate. Millions of acres of farmland are sprayed with RoundUp each year.

The end result? Monsanto: “Look at the evidence. Do they cost more? Sure. There’s always a price when it comes to advances in technology, but let’s look at the higher yields. We benefit, the farmer benefits.” When pressed about the long-term implications of GM seeds, the spokesman connects genetic modification to global benignity. “It’s nothing new, really. If anything is new it’s the fact that we are now in position to take global hunger and tackle it head-on.”

“False,” says an anti-biotech activist. “These seeds have been dubbed ‘suicide seeds’ for a reason — they cannot be used from one season to the next. Saving seeds and using them for the next harvest is an integral part of farming and always has been. Putting farmers further in debt is not tackling world hunger. How can a genetically engineered seed that results in more chemical spraying than ever and spikes the farmer’s costs be a benefit to anyone but multinationals?”

Activists have pushed for federal agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency and the Food and Drug Administration to strengthen policies and laws that would replenish biotech companies’ hold on the agriculture industry. “Are we making an impact?” one activist asks. “Yeah, sure. But it’s tough work and what we’ll eventually have to work on is not just protecting America but the third world.” In the “third world,” Monsanto can position itself not as a money-hungry foreign conglomerate but as a compassionate corporation looking to give their less developed brethren a helping hand.

Reporting from Chattisgarh, India:

There is land in central India that is ostensibly owned by those who harvest its soil, yet the St. Louis based Monsanto Corporation has co-opted the land. The farmers of this rural region have been exploited. The very seeds they plant rob the farmers of their livelihood.

In Chattisgarh, the true implications of biotechnology are clear: acres of farmland have been turned into a barren wasteland. As stated, Monsanto’s GM seeds contain what is known as the “suicide gene,” brutally ironic when one realizes that thousands of farmers in rural India have turned to suicide since the late 1990s.

“It’s impossible to fathom at first,” says one opponent of biotech multinationals, “but when you see the enslavement of these farmers in places like India, you can understand why suicide among farmers has occurred en masse.”

“Year after year it gets worse here,” says one villager. “When one year is bad it affects the next season for the farmer because saved seeds are useless. Further into debt they go and they become slaves to the seed companies.”

Monsanto: “GM seeds are a breakthrough in biotechnology which allow us to use the land we already cultivate to yield larger number of crops and, in some cases, use land that was previously thought not suited for agriculture.”

*

They exist too in the richest metropolises of the world. (Berger)

Across the river from Saarinen’s towering symbol of growth and progress is a toxic landscape. East St. Louis has been strangled in the St. Louis metropolitan area by the interstate and its residents are strangled, literally, by the toxicity of their city. Sharing a border with East St. Louis, Illinois is a municipality formerly known as Monsanto, Illinois. The Monsanto Corporation, headquartered in suburban St. Louis County, incorporated the land just south of East St. Louis in 1926 where it subsequently began producing some of the most toxic chemicals not of this earth. You are not permitted to see Monsanto, Illinois, because the village changed its name to Sauget in 1967 amidst the growing environmental movement.

Monsanto operated a chemical production facility near East St. Louis for nearly seventy years until the EPA became suspicious of the corporations’ desire to buy residential property in the surrounding community. In 1983, Monsanto and four other corporations began buying out homeowners in and around East St. Louis in order to create a toxic buffer zone — a barrier against future environmental health lawsuits. In 1990, the EPA designated half of the entire village of Sauget as a toxic Superfund site when it discovered that Monsanto had dumped PCBs and other toxic byproducts of chemical weapons production into surface waters and buried them in ditches where they proceeded to seep into the soil and groundwater.

You are not permitted to see the poisoned earth, poisoned humans.

Many suits have been filed against Monsanto yet the majority of plaintiffs have settled out of court. Settlement out of court for a lump sum is a common occurrence whenever poor people battle a giant billion-dollar corporation in the halls of the US “justice” system. These plaintiffs are products of an economic and political system that, by design, has erected and fortified walls against socioeconomic and geographic mobility. Most of the poisoned in East St. Louis are poor and African American. In the US, “minority” groups are three to five times more likely to live in dangerous proximity to toxic facilities and eight times less likely to live in suburban areas where comprehensive zoning and planning ordinances help prevent the construction of toxic production facilities.

Traveling along the interstate above East St. Louis, you do not see anything at all but the gas gauge in your SUV because you have not been permitted to look at things closely. In addition to living with a poisoned landscape, nearly forty percent of East St. Louis’s 30,000 humans live below the poverty line-three times the national average of thirteen percent. There is no such thing as the Class War in America. Ninety-eight percent of the city’s population is African American. There is no such thing as racial inequality in America.

Capitalist growth was an ideological warhead in the days of the Cold War when Eero Saarinen’s Arch was constructed. In that same era, the federal government began to construct, with little state assistance and negligible local control, the majority of interstates that encircle and segregate America’s cities. Within these cities there are other, less visible walls, which are oppressive in their own way.

*

Everywhere the walls separate the desperate poor from those who hope against hope to stay relatively rich. (Berger)

War was only over because it was now everywhere. (Weizman)

For most the state of homelessness is temporary. Many of the 37 million individuals living below the poverty line in America are homeless. Conservative estimates of homelessness in the U.S. place the figure at about 3 million. Other studies have estimated that as many as 13 million Americans are homeless and most of them reside in America’s urban areas. An estimated 100 million people worldwide are homeless at any given time.

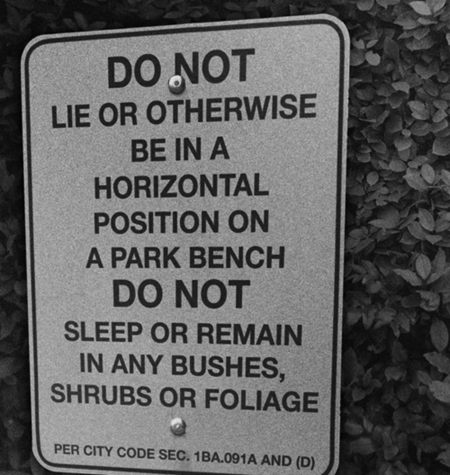

Add an armrest. Curve the seat. Transform the classic bench into a more effective design, a perch. Impose the illusion of accommodation. There is no getting comfortable.

Expand efforts. Put up signs. Do not sleep or otherwise be in a supine position.

Punish the person that has nowhere else to live. Fine them. Haul them away. Require passes to enjoy public spaces. Relocate them outside of town.

More than 200,000 veterans are homeless, with the prospect of that figure doubling, or maybe tripling, whenever the dust settles on the Iraq and Afghanistan campaigns.

The life expectancy for a homeless person is 25 years less than the average person.

The problem is not foreclosures, record-high unemployment rates, wars on several continents, the exponentially accelerated division between rich and poor. The problem is the damned benches.